Fast food workers comprise one of the lowest paid and least unionized workforces in the United States. Many work insufficient hours for low pay (PDF), without the certainty of predictable or consistent scheduling. Survey evidence shows that sexual harassment is widespread throughout the sector. Health and safety concerns, too, remain a significant problem, as the COVID-19 pandemic showed, and very few workers are covered by paid family or medical leave.

A 2021 law passed by the California legislature, the Fast Food Accountability and Standards Recovery (FAST) Act, aims to improve wages and working conditions for fast food workers. Among its novel contributions, it establishes a 10-person council composed of employers—including franchisors and franchisees—and labor representatives to establish industry-wide health and safety regulations for fast food workers across the state.

The council represents an alternative to a traditional labor union in that it aims to improve conditions across an entire workforce sector. Per US labor law, unions can organize workers at specific work sites but not across entire sectors or industries. Although this council is not exactly the same as sectoral bargaining between workers and employers across the food industry, it does provide a unique avenue for workers to improve their working conditions across an entire sector rather than franchise by franchise.

What does the FAST Act do?

The FAST Act appoints a 10-member council representing employers, employees, and the government to set minimum wage and working standards for fast food workers. There will be two members representing each of these groups: franchisors (fast food chain owners), franchisees (owners of individual fast food restaurants), restaurant workers, and restaurant worker advocates. In addition, there will be one appointee from the California Department of Industrial Relations and one from the governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development. The speaker of the California State Assembly and the chair of the California Senate Rules Committee will appoint the worker advocates and Governor Gavin Newsom, who championed the legislation, will select the rest of the council members.

The council will decide on a minimum wage for restaurant workers and is empowered to raise the wage to as much as $22 an hour by 2023. It can raise wages either in line with inflation or by 3.5 percent (whichever is lower) each year thereafter. The board must also submit a report containing proposed changes in worker standards for fast food workers, alongside their reasons for recommending these changes, by January 15 of every year. These suggested changes then become law on October 15 of the same year unless the legislature acts to prevent their implementation. These provisions would apply to any restaurant company in California with over 100 restaurants nationwide, including McDonalds, Taco Bell, and Five Guys.

Further to this bill, any city or county with over 200,000 people can now create their own miniature council, a “Local Fast Food Council.” These will not have the same power to enact higher minimum wages or increase standards, but they will be able to make sector-wide recommendations to local governments.

The council’s mandate is limited in scope. Despite evidence showing benefits of paid leave to workers, the council does not have the power to establish paid sick leave and paid vacation benefits to fast food workers. The council cannot, as it might have done under a previous version of the bill, mandate that companies offer these kinds of benefits. They can only make recommendations. The bill does, however, ban employers from taking retaliatory action against an employee if they have spoken out against an employment violation. This is an important step toward supporting job security and better workplace protections for employees.

As with benefits, the FAST Act does not allow the council to mandate rules about worker scheduling, although it can make recommendations. The fast food industry is known for its “just-in-time” and unpredictable scheduling, providing workers little advance notice and little input or control over their schedules. Fast food employees are often scheduled to work insufficient hours, which affects their ability to pay bills and make ends meet. Several cities have fair workweek laws aimed to remedy these problems, but getting employers to comply with them continues to be a challenge.

The fast food industry has long been poorly unionized

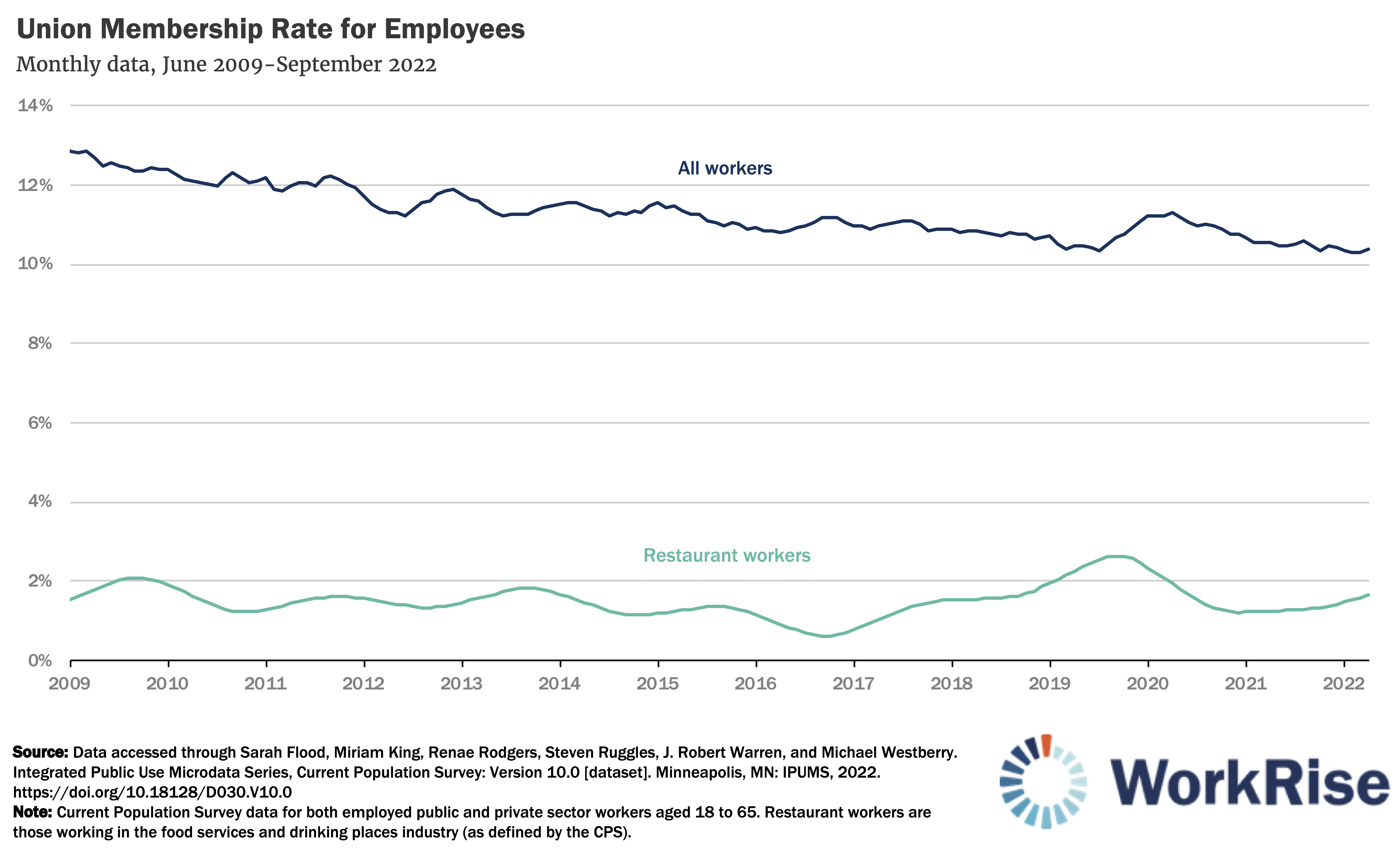

For the last 40 years, union membership has consistently fallen across the workforce, but unionization rates have always been particularly low for restaurant workers.

Several institutional reasons account for the low unionization rates in the restaurant sector. The staff at individual restaurants are often too small to attract attention from existing unions, and many employees work part time, further complicating union drives. The restaurant industry also has a high employee turnover rate, meaning employees stay in their roles for a shorter time than most workers and therefore might not have the time or interest to organize their coworkers into a union.

This reality, coupled with antiunion tactics adopted by fast food franchisors and franchisees, dissuades employees from attempting to form or join a union. Most of the impediments to unionization in the restaurant industry would exist regardless of the union protection legislation proposed by some lawmakers, such as the PRO Act. Advocacy campaigns such as Fight for $15, which are sometimes dubbed “alt-labor” groups because they work outside of traditional structures of organized labor, have brought attention to low pay and poor benefits in the fast food industry. The California legislation aims to solve the problem of low pay and poor standards in a novel, institutionalized way.

What does the research say about worker standards boards and job quality?

Research suggests that worker boards could more effectively raise incomes for middle earners as well as lower earners than minimum wage increases enacted by states or localities. As the vast majority of US earners do not earn the minimum wage, sector- and occupation-specific rules are more likely to lift the incomes (PDF) of those nearer the middle of the wage spectrum. By raising the incomes of both the poorest and those who earn slightly more, worker standard boards might help remedy (PDF) the widening of the productivity pay gap. In simple terms, it would ensure that fast food workers are paid a higher wage and would lessen the inequality between the lowest and highest earners.

Although more research is needed into the impact of worker standards boards on job quality, collective worker representation generally, such as organized labor, has been found to improve job safety and management practices, and help prevent workplace intimidation and discrimination.

Similar sectoral bargaining legislation internationally has been found to reduce workforce turnover, as employees are less likely to leave their jobs for a better paid one. Collective bargaining efforts (like sectoral bargaining) can also offer better labor standards, reduced unemployment, and reduced wage inequality.

The FAST Act goes further than its precedents

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) aimed to accommodate sector-wide negotiations over pay, though the mechanisms that allowed this have been eroded over time. Sectoral bargaining remains a common practice throughout the developed world, most popular in France, Austria, and Finland.

Worker standards boards like that in the California bill are not the same as sectoral bargaining in the traditional sense since workers do not negotiate with employers directly but rather are represented by the board. Though, crucially, they aim to achieve the same goal. Both methods implement standards for work and pay on an industry-wide basis, thereby reducing the need for unions to organize disparate, often underrepresented workers to negotiate higher pay and workers standards on their behalf.

A number of local governments and states have implemented similar structures to represent worker interests. In New York, the Commissioner of Labor has the authority to convene a wage board but has the final say on wages (PDF). Recommendations provided by the Nevada home care worker board can also be vetoed by the executive, and Michigan’s board for care workers and Colorado’s for agricultural workers (PDF) remain only advisory. As the California board’s recommendations on wages are binding and its recommendations for other standards require active dissent from the legislature to prevent these recommendations from becoming law, it has more teeth than the FLSA or state worker standards boards. The FAST Act’s impact on pay, unionization rates, employment, and other labor market outcomes will become apparent in due course.