By many measures, the United States labor market is historically tight. Employment growth is humming, job openings are exploding, nominal wages are growing, and workers are increasingly leaving jobs in favor of new employment opportunities—all signs of a robust recovery from last year’s pandemic-induced recession.

But a closer look reveals the rebound is not yet complete. Millions remain out of work in jobless spells lasting several months, a population that disproportionately includes older Americans and people of color.

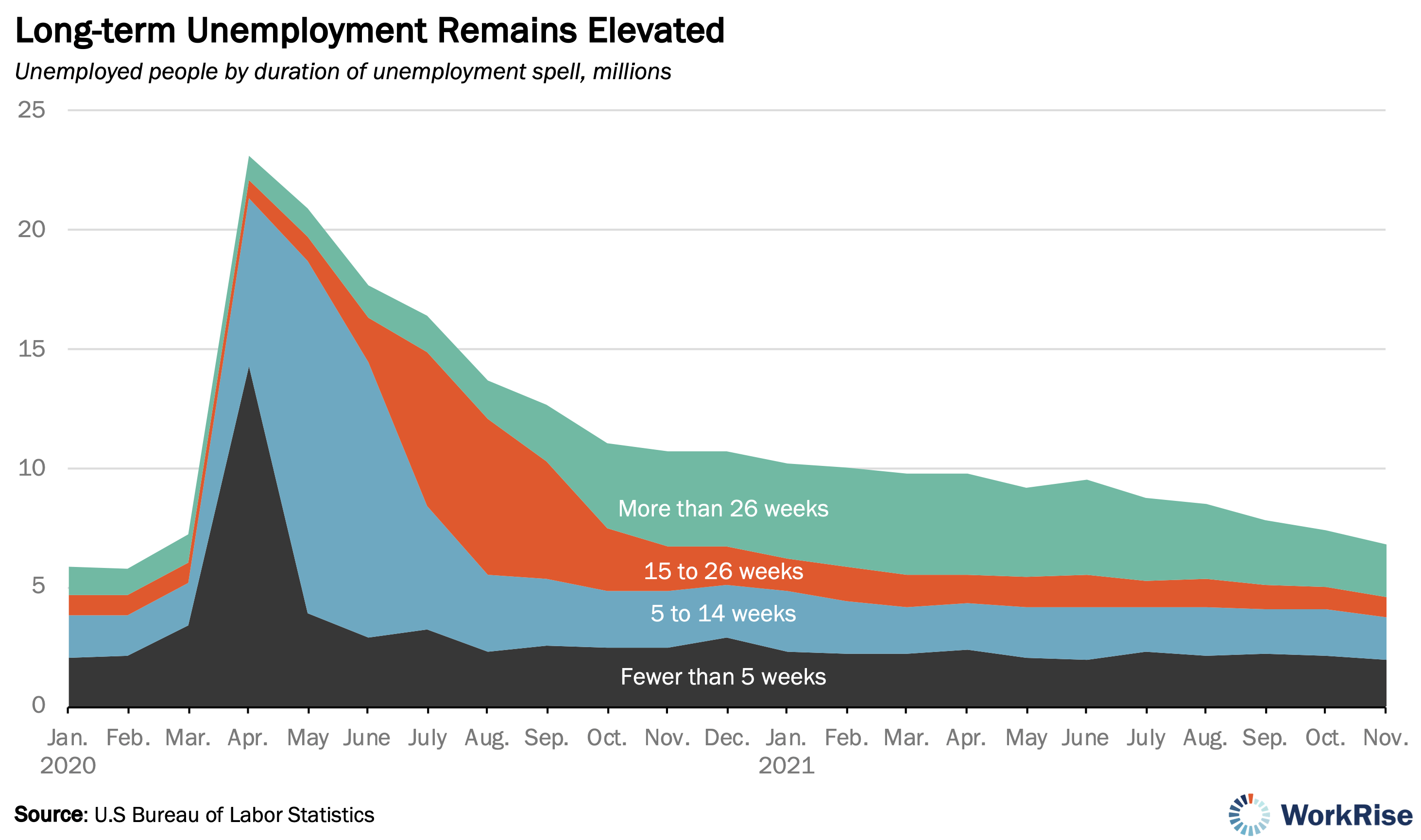

In November, 3 million active jobseekers had been without work for three months or longer—up 59 percent from February 2020. Of those longer-term unemployed people, two-thirds hadn’t worked in more than six months, even as the number of Americans experiencing shorter periods of joblessness has returned to prepandemic levels.

To examine this challenge and consider paths forward, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Public Private Strategies, and AARP last month convened a virtual event focused on long-term unemployment amid the “Great Resignation.”

The event opened with remarks from Michele Chang, deputy assistant secretary for policy at the US Economic Development Administration. It also featured a discussion between Ed Egee, vice president for government relations and workforce development at the National Retail Federation; Maria Heidkamp, director of program development at the Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University; Chad Moutray, chief economist at the National Association of Manufacturer; and Van Ton-Quinlivan, chief executive officer of Futuro Health. The discussion was moderated by Bill Rodgers, vice president and director of the Institute for Economic Equity at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

What follows are key takeaways from the convening.

The burden of long-term unemployment is not spread evenly

Certain demographic groups, such as Black workers and older people, tend to experience longer periods of joblessness, data show. In November, a typical Black jobseeker had been without work for four months, compared with roughly two and a half months for white jobseekers. About half of jobseekers ages 45 and older have been unemployed for more than four months, compared with a median jobless duration of about two months for 20-to-24-year-olds. These disparities underscore the urgency to act. “We know there is much more work that needs to be done to bring workers back, create the jobs of the future, and ensure our nation’s future economic competitiveness,” Chang said.

Several forces complicate workforce reentry for the long-term unemployed

As the COVID-19 pandemic and related concerns continue to weigh heavily on the minds of jobseekers, some may not be fully ready to embrace the employment options currently available. According to the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, 13 million out-of-work Americans are reluctant to return because of virus-induced caregiving responsibilities, fears of illness, or because they themselves are sick with COVID-19. “Job-hunting and hiring during a pandemic is certainly different, with a new calculus for workers,” Chang said. “An in-person job can bring increased risk or take a parent away from a child who is completing virtual school.”

Others may be extending their job search in hope of improved offers. For example, data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Survey of Consumer Finances show people are increasingly demanding higher pay as a condition of accepting new employment.

Even for jobseekers ready to rejoin the workforce, employment may prove elusive for those who have been without work for long periods

A large body of research shows employers are reluctant to hire individuals experiencing prolonged jobless spells. “We know from past recessions that there is a stigma attached to long-term unemployed jobseekers,” Heidkamp said. The result: as time without work continues, efforts to find employment tend to become less and less successful, an effect economists call duration dependence. “People who were long-term unemployed, in previous recoveries, were viewed as, ‘there’s something wrong with you,’” Rodgers said.

Employer reliance on automated hiring systems can perpetuate bias against the long-term unemployed

Approximately two in three midsize employers now use automated applicant processing tools, a recent survey from Harvard Business School finds, as do nearly all Fortune 500 companies. Of the programs commonly utilized, most are programmed to reject candidates based on certain characteristics, such as a gap in full-time employment, irrespective of a person’s other qualifications, according to the Harvard report. Consequently, people experiencing longer unemployment spells can be automatically screened out even if they have what it takes to excel at a job. “These people put their resumes into some black hole and then never hear back, regardless of what kind of skills they have,” Heidkamp said.

The long-term unemployed may find employer demand for occupations and skills has shifted, putting them at further disadvantage

This could be especially true as the United States continues to adapt to COVID-19, Ton-Quinlivan said. “The aftermath of the pandemic will be a crisis of mental health and behavioral health issues, which creates a whole new workforce that is needed that is not out there,” she noted. “There are a lot of shifts, and being able to move at the speed of need is going to be important.” Similarly, in its economic projections for the next 10 years, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that “structural demand in some industries and occupations is expected to shift as a result of economic changes driven by the pandemic.”

New skills are unlikely to be a panacea, especially absent more inclusive and equitable hiring practices

For the long-term unemployed, stigma and skills are layered challenges. Heidkamp recounted stories of jobseekers who, during the recovery from the Great Recession, “got the latest IT credentials, high-demand skills, and then employers would say, ‘We can’t hire them because they don’t have experience using those skills.’” Age discrimination and bias against applicants of color present yet more barriers to hiring, as do degree requirements and criminal record screens. “It’s not so much a question of a skills gap… but more of an opportunities gap,” said Heidkamp.

A sustained tight labor market could hasten a recovery for the long-term unemployed

As employers compete to hire amid strong demand for workers, they are casting wider nets and relaxing some requirements for applicants. Wages are rising, particularly for lower-paid workers, and more planned raises are on the way. The resulting terrain may be more hospitable for long-term unemployed individuals looking to reenter the workforce. Companies are “eager to hire workers of all stripes,” said Egee, who emphasized that retailers are increasingly offering improved compensation and schedule flexibility. “For employers, we have to step up to the challenge” of attracting talent, Egee added.

It appears to be working, at least so far. Although longer-term unemployment remains elevated compared with the prepandemic labor market, it is declining at a rate far faster than experienced in the aftermath of previous downturns. Following the Great Recession, it took more than 10 years for the share of the labor force experiencing unemployment longer than three months to fully recover. Less than 2 years after the onset of the COVID-19 recession, that share is already down nearly two-thirds from its 2020 peak, a much quicker pace of return. “We don’t want to lose sight of the good, which is some pretty strong labor market activity coming back from the pandemic,” Moutray said.

But whether these trends persist remains to be seen. The panel agreed sustained change is needed to ensure recovery reaches all corners of the labor market. Any less means shortchanging those most at risk of falling behind. “Whether workers really will end up showing more leverage, having more leverage after this, it’s not clear,” Heidkamp said.