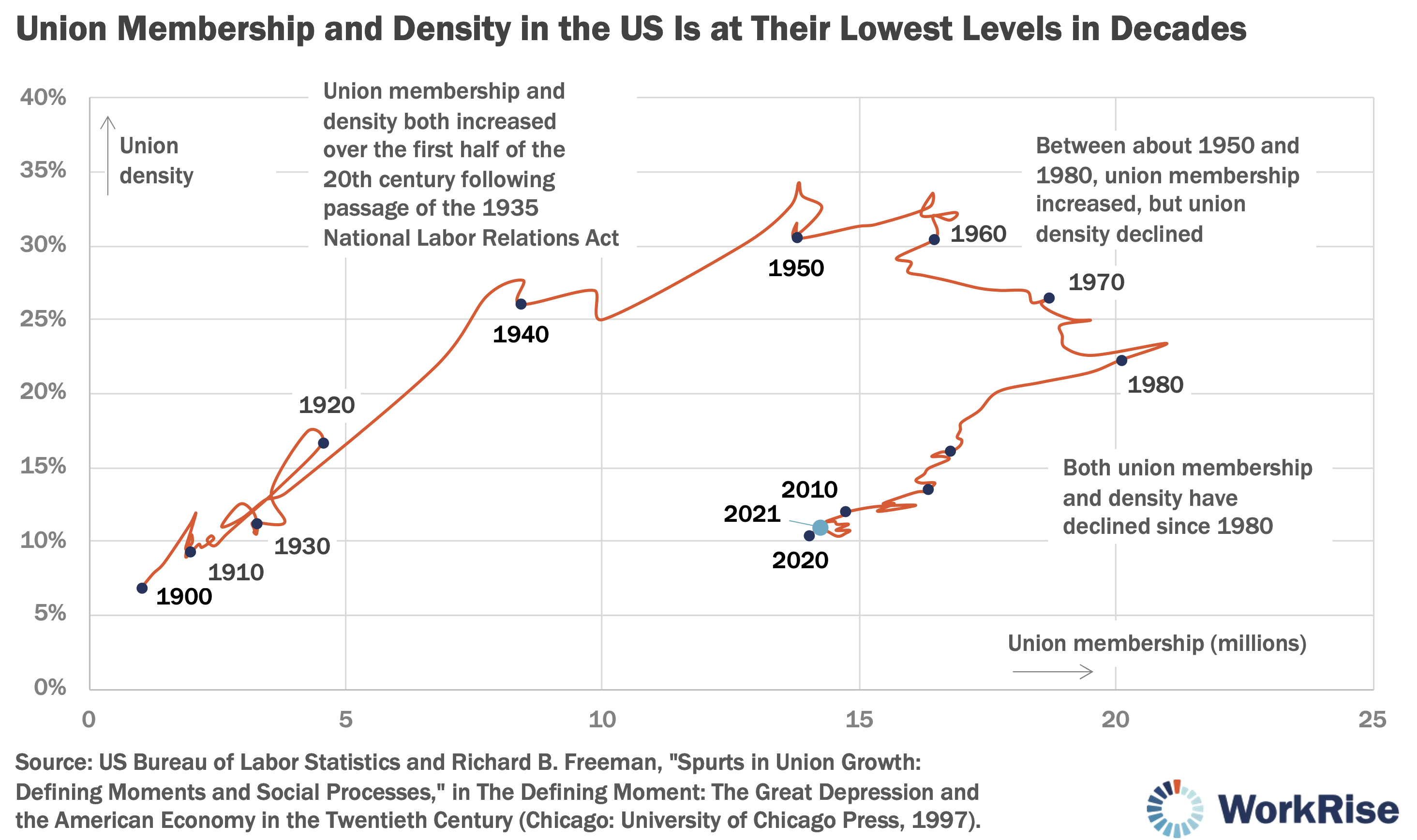

In 2021, Americans’ favorability toward labor unions reached a 56-year high. The groundswell of public support—with nearly 7 in 10 people expressing approval of unions—came amid a turbulent year for workers, a high-profile period for collective organizing efforts, and a White House effort to boost union strength. Yet, despite heightened focus on the conditions of work and workers’ voice and power on the job, new data show 2021 also brought a decline in union membership. By one measure, unionization is less common now than at nearly any point in over 100 years.

What is the state of union participation in the United States today, and what does it mean for economic mobility and security? Here are three key things to know.

Union membership continues to dwindle near historic lows

From 2020 to 2021, the unionized workforce shrank by 241,000—even as the economy-wide employment level grew more than 6 million, according to data released in January by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The ranks of unionized workers totaled just over 14 million, close to a historic low. Not since 1950 (PDF) have there been fewer union members in the US workforce.

Last year’s union membership rate, which accounts for employment growth in the economy at large, matched 2019 for the lowest level experienced in more than 100 years, with 10.3 percent of American workers belonging to unions. (The membership rate rose in 2020, but the number of union members fell, an artifact of the unprecedented job loss and compositional changes to the workforce caused by the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic.) To find union density as sparse as it is today, one must look back to 1916—nearly two decades before the enactment of the National Labor Relations Act, the 1935 law granting workers legal authority to organize and bargain collectively with their employers.

The ebb in unionization is most evident among private-sector workers. In the early 1970s, private-industry workers and government employees belonged to unions at roughly equal rates; approximately 1 in 4 workers in both sectors was a union member. In the decades since, private-sector unionization has declined precipitously, reaching a low of 6.1 percent in 2021. Union participation in the public sector rose in the latter half of the 1970s and has held relatively constant since, currently at 33.9 percent. Even so, the union membership rate among government workers has steadily and gradually eroded over the past decade.

Petitions and elections to form new unions are becoming less common too. A petition is filed with the National Labor Relations Board once at least 30 percent of eligible workers in a nonunion establishment have registered their support for unionizing. Last year, workers at private-sector companies filed 1,330 petitions to hold elections on unionizing their workplaces, compared with 1,702 petitions in 2019 and 2,285 petitions in 2010.

Support for unions is growing, indicating a widening “representation gap”

Despite the erosion in membership, evidence suggests support for labor unions is rising. In 2021, 68 percent of Americans said they approved of labor unions, the highest level recorded since 1965, according to Gallup. Support bottomed out at 48 percent in 2009 and has been rising steadily since, the polling organization found. Similarly, public opinion data from Pew Research Center shows Americans increasingly say the decline in union membership is bad for both workers and the country.

The appeal of collective organizing is also growing among workers themselves. Nearly half of nonunionized workers would vote to join a union if given the opportunity to do so, according to the findings of a nationally representative 2017 survey by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. If the same share were to hold this preference today, the number of union-favoring workers not currently in a union would total close to 57 million—four times as many workers as there are union members. Put differently, for every unionized American worker, there are approximately four who wish to join a union.

In similar surveys conducted in 1977 and 1995, one-third of nonunion workers said they would like to become union members. The heightened interest in unions shown in the 2017 survey, paired with the ongoing erosion of union membership, indicates a widening “representation and participation gap” between workers’ desire for voice and influence and the real options available to them.

In another survey conducted in 2021, American Compass, a research and advocacy organization that has been critical of how labor unions operate in the US, polled a representative group of nonsupervisory workers at for-profit, private-sector firms to determine their levels of support for various forms of voice and representation. When asked whether they would vote to back a union effort at their workplace, 35 percent said they would and another 34 percent said they were uncertain. These responses are generally consistent with a participation gap, but they also suggest many workers lack information about unions and may be open to other forms of workplace representation.

Declining bargaining power has consequences for workers and the broader economy

The continued decline of labor union membership and the broader trend of eroding worker bargaining power have important implications for economic mobility, job quality, and household financial security.

Unions tend to improve compensation for workers, lifting more people into the middle class and bolstering economic opportunity. Research demonstrates that these benefits are felt across the economy, not just among workers represented by collective bargaining agreements. That’s in part because unions cause positive spillover effects not confined to the boundaries of unionized firms. These effects occur when nonunion employers raise the bar to compete with unionized companies or to preempt an organizing effort by dissatisfied employees—a dynamic that suggests as union density declines, so too will the competitive impetus to boost compensation. Research indicates unions also reduce racial inequality, with one study estimating the gap between wages for white and Black workers would be up to 30 percent smaller if union membership today were as common as in the 1970s.

In addition to their effect on worker compensation, unions can enhance other aspects of job quality such as workplace safety and work-life flexibility, research shows. Several studies have examined the impact of unionization on the enforcement of occupational health and safety laws, finding positive effects. Another line of evidence finds that when unions focus on securing work-life accommodation practices such as flextime, telecommuting, and personal and family leave, workers’ access to these benefits increases.

Although evidence generally indicates unions benefit lower-wage workers, the sources of these gains, and the broader economic effects of unions on firms, labor markets, and the economy overall are the subject of active empirical research. One body of evidence indicates a portion of the benefit accruing to workers represents a transfer of resources from managers and owners. Another investigates the impact of unions on workplace productivity, with some studies indicating unions improve productivity, which then supports gains in compensation and job quality.

The causal channels between unionization and improved worker outcomes are an important subject for research. Stronger evidence can inform policymaking and close the representation and participation gaps workers experience on the job.

An earlier version of the graph in this post included a line connecting the data points for each year and a smoothed line that illustrates the overarching trend. For clarity, we removed the smoothed line (corrected 3/7/2022).

Starbucks employees wait for results of a vote count, on December 9, 2021 in Buffalo, New York. - The ballots have been cast and employees of three Starbucks cafes in Buffalo have created the first union at outlets owned by the retail coffee giant in the United States. (Photo by ELEONORE SENS/AFP via Getty Images)